King Philosophy Core Elements

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s King Philosophy

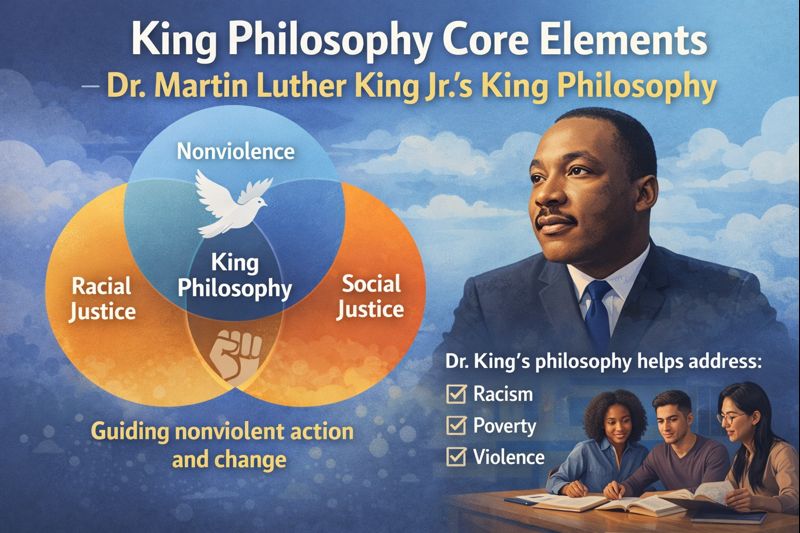

Exploring Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s philosophy equips students with essential tools to dissect racism, poverty, and violence, simultaneously outlining actionable pathways for nonviolent societal transformation. College students researching nonviolent resistance methods in civil rights history frequently turn to this framework for structuring compelling arguments in their assignments. For college essays, classroom debates, and community projects, it connects ethics, activism, and social theory in ways that remain urgently relevant today.

King Philosophy overview

The King Philosophy is a systematic approach to confronting injustice that combines moral principles with practical strategies rooted in nonviolence. University learners seeking comprehensive guides on integrating ethical theories into social activism projects often explore this philosophy to develop nuanced perspectives. It teaches that genuine social transformation depends on rejecting physical and spiritual violence while pursuing justice, reconciliation and the creation of what King called the Beloved Community. Academics examining the evolution of justice-oriented movements benefit from applying these ideas to case studies in global conflicts.

At its core, the philosophy assumes that systems can change, opponents can become partners, and movements must embody the inclusive, just society they seek to build. Graduate researchers analyzing intersections of ethics and policy reform regularly reference this core assumption in their dissertations on inclusive societies. Students can use this framework to interpret past civil rights campaigns and to evaluate current struggles over policing, climate justice, gender equity and more. Professors assigning papers on contemporary equity issues encourage incorporating this lens to foster critical thinking skills among learners.

The Triple Evils

King described three interconnected forces that obstruct a just society: poverty, racism and militarism, often called the “Triple Evils.” Undergraduate scholars investigating structural barriers in modern economies commonly apply this concept to deepen their understanding of interconnected injustices. Poverty captures the structural conditions that keep people trapped in unemployment, low wages, hunger, inadequate housing and limited access to education and health care.

Racism refers not only to explicit hatred but also to stereotypes, discriminatory laws, biased institutions and everyday practices that devalue people based on race or ethnicity. Doctoral candidates studying institutional biases in education systems frequently draw on this definition to support their theses on systemic reforms. Militarism encompasses war, state violence, interpersonal brutality and cultural habits that normalise force as the main way to resolve conflict. International relations students exploring alternatives to militaristic policies often use these insights to propose peaceful resolution strategies in their coursework.

For King, these evils reinforce one another: racial hierarchy justifies economic exploitation, and both are defended with violence or the threat of violence. Social science majors dissecting global inequality patterns regularly employ this reinforcement analysis in their research proposals. Analysing contemporary issues through the Triple Evils helps students trace how inequality, prejudice and coercion operate together in local and global contexts. Community organizers planning advocacy initiatives find this tracing method essential for identifying root causes in diverse settings.

Six Principles of Nonviolence

Nonviolence, in King’s philosophy, is not passivity but an active, disciplined way of resisting injustice that demands courage and strategic planning. Activists preparing workshops on ethical resistance techniques often adopt this active interpretation to inspire participants in community-building efforts. Educators and activists often summarise his ethics into six guiding principles that shape attitudes, tactics and long‑term goals.

- Nonviolence as a courageous way of life: It requires resisting the urge to retaliate, using inner strength and moral conviction to confront injustice without inflicting harm.

- Nonviolence seeks friendship and understanding: Campaigns aim to open dialogue and build relationships that can outlast a single protest or policy fight.

- Nonviolence opposes injustice, not people: Activists target oppressive laws, institutions and practices while recognising the shared humanity of those who support or benefit from them. Peace studies learners debating human-centered approaches to conflict resolution highlight this principle in group discussions to emphasize empathy’s role.

- Nonviolence accepts suffering as transformative: Willingness to endure hardship for a cause can expose injustice, deepen solidarity and reshape public opinion.

- Nonviolence chooses love instead of hate: King emphasised agape, or unconditional goodwill, as a force that can disarm enemies and heal fractured communities.

- Nonviolence trusts that justice is ultimately achievable: The philosophy is grounded in hope that moral and spiritual forces, along with human effort, can bend history toward greater justice.

For academic work, these principles give students a vocabulary for comparing Kingian nonviolence with other ethical systems, such as just war theory, restorative justice or contemporary abolitionist movements. Ethics course participants comparing nonviolent ethics to alternative frameworks rely on this vocabulary to construct balanced comparative essays.

Six Steps of Nonviolent Social Change

To move from abstract principles to practical action, King’s followers developed six steps of nonviolent social change that outline a repeatable process for campaigns. Leadership development trainees designing community intervention plans commonly reference these steps to ensure structured and ethical approaches. These steps help students and organisers think strategically about how to address campus, community or policy‑level problems.

- Information gathering: Campaigns begin with careful research into the history, causes and impacts of a problem, including perspectives from those most affected and from opponents.

- Education: Activists share their findings through teach‑ins, articles, presentations and conversations, making the injustice visible to wider audiences. Environmental justice advocates compiling reports on local issues incorporate this education phase to mobilize broader support networks.

- Personal commitment: Participants examine their motives, cultivate discipline in nonviolence, and prepare emotionally and spiritually for potential risks.

- Discussion and negotiation: Leaders attempt to resolve the issue through dialogue, presenting clear demands and constructive proposals to decision‑makers.

- Direct action: If negotiation fails, nonviolent tactics such as marches, boycotts, sit‑ins, petitions or strikes are used to create “creative tension” and push for change.

- Reconciliation: The long‑term goal is a just resolution that restores relationships, integrates former opponents into the new order and reduces the likelihood of future conflict.

Students can map historical campaigns—such as bus boycotts, voting‑rights drives or anti‑war protests—onto these steps, or design hypothetical projects using this sequence in assignments and capstone projects. Capstone project designers mapping real-world scenarios to nonviolent processes use this method to demonstrate practical applications in their portfolios.

The Beloved Community

The Beloved Community is King’s vision of a society where justice, equality and mutual care shape political, economic and cultural life. Philosophy majors delving into utopian social models frequently examine this vision to critique existing societal structures. In this concept, conflict still exists, but it is addressed through nonviolent methods that honour the dignity and worth of every person.

Scholars describe the Beloved Community as rooted in agape love, inclusive fellowship and structures that eliminate racism, poverty and all forms of violence. Cultural studies researchers investigating inclusive community models often highlight these roots in analyses of modern cooperative initiatives. Features often highlighted include radical hospitality, fair distribution of resources, participatory democracy, and peace that is inseparable from justice. Interdisciplinary teams studying sustainable development integrate these features into proposals for equitable urban planning.

For students, the Beloved Community functions both as an ethical ideal and as a practical horizon that guides everyday choices in classrooms, workplaces, neighbourhoods and digital spaces. Online learners enrolled in diversity and inclusion courses apply this function to evaluate digital community dynamics. Linking course content to this vision encourages critical reflection on how institutions could be redesigned to promote belonging rather than exclusion. Faculty developing curricula on social ethics link this vision to foster reflective practices among diverse student groups.

Applying the King Philosophy today

King’s framework offers analytical tools for understanding contemporary issues such as mass incarceration, refugee crises, digital harassment and climate‑related displacement. Policy analysis students addressing global displacement challenges regularly utilize this framework to formulate humane response strategies. Researchers and practitioners draw on the Triple Evils, the Six Principles and the Six Steps when designing campaigns that centre marginalised communities and aim for structural reform rather than symbolic change alone.

In higher education, the King Philosophy can inform service‑learning projects, conflict‑resolution workshops, human rights courses and interdisciplinary research on peace and justice. Adult education facilitators incorporating peace studies into workshops draw on this philosophy to enhance participant engagement. When students engage deeply with these ideas, they gain not only historical insight into the civil rights movement but also practical frameworks for ethical leadership and community organising in the twenty‑first century. Emerging leaders in nonprofit sectors engage with these ideas to build sustainable organizing skills for long-term impact.

Integrating King Philosophy in Modern Academic Research

Incorporating Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s philosophy into contemporary academic research empowers scholars to address ongoing challenges like systemic inequality and environmental injustice through a lens of nonviolent transformation. Researchers exploring the triple evils in the context of global pandemics and economic disparities discover innovative ways to advocate for policy changes that foster the beloved community ideal. Applying the six principles of nonviolence and the six steps of social change in theses on urban renewal projects helps students propose solutions that prioritize reconciliation and inclusive growth. This integration not only enriches scholarly discourse but also equips future activists with timeless strategies for building equitable societies amid evolving social dynamics.

Works Cited

Burrow, R., Jr. (2018) ‘Martin Luther King, Jr.’s theology of the cross and the praxis of nonviolence’, Theology Today, 75(1), pp. 41-53. doi:10.1177/0040573618754744.

Nepstad, S. E. (2019) Nonviolent struggle: Theories, strategies, and dynamics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Available at: https://academic.oup.com/book/26648 (Accessed: 15 January 2026).

Long, M. G. (2021) ‘Martin Luther King Jr.’s vision of the beloved community in contemporary social movements’, Journal of Religious Ethics, 49(2), pp. 315-335. doi:10.1111/jore.12356.

Jackson, T. F. (2022) Becoming King: Martin Luther King Jr. and the making of a national leader. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky. Available at: https://www.kentuckypress.com/9780813196930/becoming-king/ (Accessed: 15 January 2026).

Wills, R. E. (2020) Martin Luther King Jr. and the image of God: Implications for nonviolent activism. New York: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780190060817.001.0001.